“Don’t worry – today, and every year going forward, 25 April will be a national holiday.”

Captain Salgueiro Maia attempts to console a cleaning lady who, arriving for her early morning shift at the Post Office facing Terreiro do Paço and upset that soldiers are blocking her from entering her workplace, insists on speaking to the person in charge.

For a few hours on April 25, 1974 several dozen Captains in the Portuguese military seized control of the military from their more senior officers. In those few hours they used that control to nearly bloodlessly topple Europe’s oldest totalitarian government, immediately establish freedom of the press, freedom of political parties, free all political prisoners and successfully protect a process aimed at turning Portugal into a free, democratic society within a year.

Their action is known as the Carnation Revolution. Ever since, April 25th has been a Portuguese national holiday. Freedom Day.

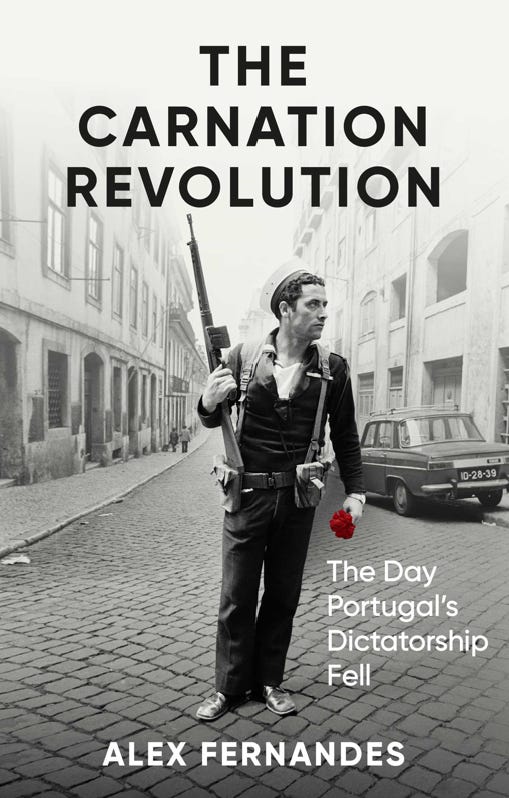

The improbable and inspiring story is told in Alex Fernandes’ “The Carnation Revolution: The Day Portugal’s Dictatorship Fell”. It is utterly gripping.

While outwardly the story of the day itself, how it came to be and what came after, rich insights emerge into leadership, the brotherhood of arms, the development and evolution of social movements, military coups, counterinsurgency, decision traps, middle management, human psychology, group decision making, action under uncertainty and more.

Above all, Fernandes’ book is an extended love letter to the people of Portugal. In learning the story of the Carnation Revolution and the passionate, argumentative, audacious and proud people on all sides, you can’t help but fall in love yourself.

“I only know how to shoot people with guns in their hands.”

Lieutenant Assis Gonçalves refuses the order to shoot the hundred or so participants in his custody of a just-failed 1927 left-wing coup

Portugal’s dictatorship began in 1926 when a military coup, backed by a majority of the population, ended sixteen years of chaos during which Portugal had forty-five governments and seemingly unending economic crisis. The new military government quickly established a right-wing, authoritarian state. The economic situation did not improve and after a failed left-wing coup in 1927, realizing it didn’t have the technical expertise to govern, the military ceded control of finances to a popular right wing academic and orator, Doctor António de Oliveira Salazar. Intelligent, analytical, politically savvy, economically knowledgeable and skilled at using the media, Professor Salazar balances the government’s books and is hailed by the international press.

Salazar accumulates successes and accolades, adroitly using them to gradually accumulate more power. By 1932 became the incontestable head of the government. Salazar continues the ban on political parties, expands state censorship, bans strikes, requires loyalty oaths from government officials, builds a remarkably capable secret police and effectively subjects labour unions to government control.

While Salazar’s right wing authoritarian dictatorship has similarities with Franco in Spain, Mussolini in Italy and Hitler in Germany, Salazar is more serious school teacher than strong man, nor is there street thuggery. Salazar fashions a right-wing technocracy, supported by the military, the Catholic church, Portugal’s economic elites and a very effective secret police. Lieutenant Gonçalves, quoted above for refusing to shoot prisoners, is rewarded for his insubordination by being named Salazar’s secretary and becomes a key Salazar advisor.

As happens again and again in Fernandes’ story, individual Portuguese ostentatiously and stubbornly refuse to act as expected or prudent and, as a result, history changes course. Lieutenant Gonçalves’ indignant insubordination is but one example.

The effectiveness of Salazar’s secret police and the consistent failure of charismatic but laughably inadequate attempts at the regime demoralize the opposition, who lose faith in the idea that the regime could be overthrown. Salazar’s dictatorship has managed a stable equilibrium. Like China, Cuba or North Korea, the regime could have been sustainable until today but for one fatal weakness. Central to the regime’s identity is its self-perception as proud heir and custodian of hundreds of years of Portugal being a global force for civilization, as embodied by Portugal’s globe spanning overseas provinces.

The first major signs of difficulty in the overseas provinces begin in 1961. After declining India’s request that Portugal hand over its territories in India, India simply masses overwhelming force and seizes them. That same year, an insurgency begins in Angola aimed at independence.

Portugal’s universities are hotbeds of underground resistance to the regime. With charming naivety, the regime expects carefully selected overseas elites, after attending Portuguese universities on scholarships, to join Portugal’s civilizing mission. Down the street from the military college where Portuguese officers are trained, overseas students learn anti-colonialism and self-determination, returning to their homelands to start, or join, insurgencies and national independence movements.

From 1961, the regime becomes like the proverbial frog in the pot with the temperature slowly rising. Insurgencies grow, particularly in Guinea, Mozambique and Angola. Pressured in part by fearful Portuguese emigrants in the overseas provinces, Portugal’s military response grows in proportion. Further, an aging Salazar, while utterly secure as leader, is increasingly inactive. He dies in 1970 and is replaced by Marcelo Caetano, who continues the regime’s core approach as right-wing technocracy fully committed to its overseas provinces.

In 1961 two years of conscription is introduced. In 1963 the four year officer training program is shortened to three years by eliminating the summer breaks. In 1967 the term of conscription is increased to four years. By 1970, 40% of the Portuguese government budget is dedicated to fighting the insurgencies abroad. In 1971 the age of conscription is lowered to 18.

A founding member of NATO in 1949, Portuguese officer training focuses on a standard NATO-Soviet clash. Senior generals succeed by cultivating the political leadership over effectively leading the military. Efforts to refocus the officer training curriculum from prestigious NATO-style warfare toward counterinsurgency go nowhere. Hard hitting, honest reports from the field are massaged as they work their way up the hierarchy, so by the time they reach senior levels all is reported as going well with just a little more push required. This reality distortion field causes orders and directives from distant high command to be increasingly divorced from reality by the time they make it to the troops facing the insurgencies. To junior officers in the field, the military leadership becomes known as ‘the rheumatic brigade’.

Insurgencies are wars of junior officers. The Captains of the Portuguese military are the most senior officers who consistently experience real conditions on the ground. They are the ones planning and leading the extended company sized combat operations that characterize counter-insurgency operations. The situation in the field is not at all what the officers learned in school. On multiple combat tours, the officers’ experience is mines, ambush, the need to win hearts and minds and insurgents who quickly blend into a sullen local population or flee to safe haven across an international border. Portuguese expatriates are demanding and ungrateful and the local population shows little interest in, or need of, their civilizing mission. Many Captains have a story of their epiphany, the experience that caused them to realize that the wars could not be won and that Portugal must leave.

Officers learn on the ground and from each other, returning to combat tour after combat tour after combat tour. Captain Salgueiro Maia, quoted at the top and who we will hear of later, has done five combat tours and is due shortly for deployment into a sixth. Awaiting orders home on his most recent combat tour he was instead sent on a six day emergency operation that turns into forty days of grueling conditions with his soldiers in the wilderness of Gineau-Bissau. Waiting for him on return is a five month emergency extension. The Army just doesn’t have enough experienced officers to meet its growing needs in the field.

Eighteen year old Portuguese conscripts are shocked to arrive in theatre and discover a reality on the ground completely unlike the glorious Portugal helping grateful locals that they had been taught in school and exposed to in Portugal’s heavily censored media. Insurgent propaganda makes more sense than the clearly wrong and out of touch information coming from Portugal’s media. Like subordinate outsiders everywhere, the Portuguese educated insurgents understand the rulers better than the rulers understand themselves.

By the time a Portuguese officer has reached Captain, he has lived this reality for years, survived multiple combat tours and planned and led dozens of operations, sharing the misery in the field along side their soldiers. For eighteen year old conscripts, their Captains embody superb competence and the key to their survival. Their Captains know how to win and how to keep their soldiers alive while doing it. In a suddenly uncertain world, it is their Captains they can trust.

By the early 1970s, continuing to strain to meet the rising demands of the insurgencies, the Portuguese government has not yet realized it has reached the limit of its capacity. The overstretched military is unable to cover everything and the insurgents succeed by striking where the military is absent. Not able to blame the regime, the state controlled media and Portuguese emigres in the overseas territories blame the military. Junior officers walking down the street or sitting in a cafe in Portugal start getting harangued by members of the public for the military’s failure to win the wars. For officers suffering in a war they don’t believe can be won and don’t even think should be fought, who believe deeply in the honour of their military calling, this seriously grates.

The situation is unsustainable. Something will change. The question is what.

Anxious to show it is taking action, in April 1973 the Portuguese government announces a Congress of experienced veterans to give advice on how to handle the insurgencies. Frustrated that their own senior leadership seems deaf to their reports, junior officers see this as a welcome and overdue opportunity to give the government essential feedback about the wars. However, none of the officers selected for the Congress has combat experience more recent than the mid-1960s. Many active duty Captains abroad and in Portugal attempt to have some of their number included. All requests are denied. Several officers self-organize into an uninvited delegation and are refused entry.

Frustrated by this, while the Congress is in session a group of Captains serving a combat tour in Guinea draft a brief telegram to the Congress organizers criticizing the ability of the Congress to reach sound conclusions given the lack of relevant representation. After an intense two day effort, more than 400 junior officers from all branches of the Portuguese military sign the telegram. The Congress organizers ignore the telegram and in June delivers a report endorsing the existing government approach to the insurgencies.

It is June, 1973. The telegram has failed. However a new thing now exists, ‘the Captains’. In failing to influence the Congress, the Captains of the Portuguese military have discovered that they not only fundamentally agree about their experience, but that they can quickly organize and act. In so doing, they finally feel like there is something they can accomplish. Only looking back later do they recognize that ‘the Captains’ as a grouping had been born.

From this birth follows a series of failed challenges over the next nine months. Yet in each failure the Captains learn more about their options to solve the insurgencies, what they are capable of and what they intend to do. Ironically, each failure by the Captains strengthens them while, as failures, they reinforce the regime view that these naive upstarts are being successfully managed. It is like an action movie where the hero spends the whole movie losing and narrowly escaping until the end, with failure no longer an option, the battered hero demonstrates mastery and achieves spectacular, satisfying success.

Fernandes ably describes the process. His story of the newborn’s birth and tottering yet rapid development is astonishing and informative. This review will outline a few steps along the meandering path the Captains took from June 1973, failing to give policy input to a Congress, to the following April when they deftly overthrow the government in a way designed to reform Portugal as a free society.

It is July, 1973. Notwithstanding a Congress report telling the government it was on track, the military recognizes the non-sustainability of emergency combat tour extensions of experienced officers. Insurgencies are wars of Lieutenants and Captains. More Lieutenants and Captains were needed and the military can not wait for the accelerated three year officer academy program to fill its shortfall. The military announces Ordnance 353/73. High potential conscripts, suitable as officers, would receive eight months of training followed by a combat tour as a junior officer. Conscript officers who perform well during their compulsory military service would be eligible for admission into the regular military.

Like bad news everywhere, the regulations are issued in the summer when few would notice. However, as is the case for middle managers in any organization, when a change pertains to their promotions, the middle managers pay attention. Close attention. Captains figure out that, according to the new rules, some conscript officers would be eligible for promotion to Major or Lieutenant Colonel sooner than Captains with multiple combat tours and graduation from three years of accelerated full military college.

Incompetent leadership forcing them to fight endless unwinnable wars was one thing, but rules that let some non-volunteer officers with less education and experience get promoted earlier? That is going too far! No organization is necessary. The military leadership is bombarded by representations from Lieutenants and Captains throughout the military.

“Be careful with the Captains. They are dangerous, given that they are not yet old enough to be bought.”

Marcelo Caetano, Portugal’s ruler

Ordnance 353/73 sparks a range of actions and counter-actions over the coming months that result in the government changing how promotions were to be calculated, implementing a major pay increase for all officers and believing it had resolved the immediate problem.

For the Captains, the repercussions from Ordnance 353/73 include the creation of a formal but secret movement of Captains and the discovery that they can speak frankly to each other, without fear of denunciation. As a demonstration of commitment, hundreds of Captains submit signed, undated resignation letters to a secret steering committee. Subcommittees of Captains representing all armed services actively meet in secret. Concerns about promotion formulas were the trigger, but it is impossible to meet and not talk about the wars. Unknown to the government, ending the wars naturally emerges as a new consensus priority and sufficient reason for the Captains to continue to work together, notwithstanding the salary increase and fixes to the promotion rules.

Overthrowing the government, however, is not a serious option. Indeed, in the process that led to the mass preparation of resignation letters, as their first decision each subcommittee of Captains immediately rejects the idea. But now the idea is there.

Through the process, the Captains also learn that while they can trust each other, they can not be sure of anyone else. The Majors, Lieutenant Colonels and up are mobilized by the military to try to convince the Captains of the merits of the regime’s efforts. Repeatedly hearing the corporate talking points from their bosses makes it hard to imagine bringing the bosses into the circle of trust. Similarly, many Lieutenants have not yet reached their epiphany. It will come, but not usually after only one or two combat tours. Most Lieutenants are not ready to be trusted.

So, it is a movement of Captains.1

“You haven’t got generals, you haven’t got brigadiers, you haven’t got colonels, you haven’t got lieutenant colonels, you might not have majors, but I guarantee that I can find you captains!”

Captain Vasco Lourenço

Safe in a bubble of trust, energized by the discovery that they need not censor their words or thoughts, Captains speak to each other with blunt frankness, regardless of where they are on the political spectrum. A small number of Captains advocate overthrowing the regime, but this is seen by most as understandable venting and crazy talk. Has it really come to that? Plus, where would they find Generals? All the Generals seem to be acting vigorously in defence of the regime.

Having shifted their focus to the elephant in the room, the insurgencies and their solution, the Captains create various subcommittees which consider and freely debate the challenge. Inevitably, in the heady new atmosphere of any topic is safe to raise, considering the problem of the insurgencies takes deliberations beyond the insurgencies themselves.

By March 1974, the Captains have reached far reaching political recommendations that, presented cold, would have been immediately rejected by most Captains as too far reaching. However, the collective deliberation process in which the recommendations emerge instead makes them inescapable. The Captains recommend offering independence to the overseas territories, the withdrawal of the Portuguese military and, in Portugal itself, the implementation of political freedom and democracy.

At this point, though secret, the Captains’ movement has been active long enough that the regime knows it exists and starts to sense it has become interested in more than promotion eligibility rules. Like every other case, it can only be a matter of time before it is well identified by the regime’s notoriously competent security apparatus and broken up.

Clearly trained more in military than political matters, The Captains decide they have a duty to present their recommendations to their leadership (!!) and agree on a plan to present them to the military leadership on March 18th and then the political leadership on March 25th. With naive enthusiasm, the Captains print two thousand copies. As would have been obvious to any politically astute person, they do not get a chance to deliver them. Beginning a week of bad news, the military somehow identifies four of the most involved Captains by name and on March 8th orders their immediate deployment abroad.

Before the end of the following month, the Captains will have seized the military and overthrown the government.

All Captains are outraged at the depolyments abroad. Three of the four Captains refuse to deploy and are sent to military prison. The first Captain to arrive is warmly greeted by his colleagues running the prison, who first misunderstand his arrival as a friendly visit. The imprisoned Captains receive concierge treatment. As usual, higher levels in the military are oblivious to the gap between actual conditions on the ground and what they assume is happening.

"What you have there isn't a plan of operations, it's nothing. It's completely inconsistent. We like to act seriously, when there's a serious plan and serious possibilities of success."

Captain Cristóvão Avelar de Sousa, demonstrating the diplomatic finesse of a typical Portuguese Captain, suggests the March plan for a coup could be improved

While the formal Captains’ structure considers next steps, angry at the preemption of their political recommendations and the measures against their colleagues, several Captains take the initiative to throw together an operation plan for a military coup based on six army units they believe would join. The plan is shared with several more Captains who identify numerous critical flaws. As the planners agree that more work must be done, other Captains come forward offering their units for a coup.

While the political recommendations were the result of months of deliberations and many formal decision processes, there is no discussion about a coup or even decision to proceed with one. With the suppression of the political program and arrest/deployment of colleagues, consensus is implicit that a coup is the next step.

On March 14th, Portugal’s National Assembly passes a motion doubling down on winning the insurgencies in Africa. Military leadership from all branches of the armed forces line up in a photo op supporting the motion. On state television, one by one the generals assure the political leadership of the full support of the Armed Forces. Only two generals are missing. The next day the government announces that those two generals have been fired. Now the Captains know of two generals they can trust! However, though they do not inform the authorities of the clandestine approach by the Captains, neither General is ready to consider a coup.

Meanwhile, the original flawed operation plan for a coup takes on a brief life of its own. Some Captains extremely keen on a coup believe the plan is good enough despite its flaws. They are confident in their units and their colleagues. While communications by phone tree and one on one relay are adequate for the slower processes of discussing, drafting and agreeing on resolutions, they are completely inadequate for military operations. Through an excess of zeal and misunderstanding facilitated by the primitive slow motion communication, on March 15th Captains of the 5th Infantry Regiment (RI5) misunderstand that the coup is on. Not wanting to leave their colleagues in the lurch, they precipitously arrest their commanding officers and race out to Lisbon with their soldiers, all of whom choose to follow them. However, unknown to RI5’s Captains, RI5 is not racing to catch up. RI5 heads out alone.

Operating well inside the military leadership’s observe, orient, decide and act loop, other Captains intervene to stop RI5 almost before the military leadership understands what is happening. With brisk efficiency and seeming unhesitating loyalty, the other Captains’ units return RI5 to barracks. The generals, focused on reassuring the political leadership, accept credit and report their swift and decisive action to the political level. The military leadership makes the mistaken assumption that the units involved in turning back RI5 are loyal and can be trusted. RI5’s Captains join their colleagues in military prison.

RI5 provides an accidental dress rehearsal for April 25th. Already adept at rapidly drawing lessons from experience, RI5’s failure provides the Captains invaluable insight about running a coup and how the government would respond. Many of the units the military leadership calls out in response to RI5 are already committed to a coup. Once again, the Captains’ failure is a set up for success.

The barrage of bad news during that week in March is when most Captains realize that it really is entirely up to them. Giving up is not an option, so once they lose hope of having a General they realize they don’t need one. Anything within the military is already controlled by a Captain, it is just a question of figuring out what they need and stitching it together. The Captains now recognize that can control the military all by themselves, if they so choose.

Less able to resist the pressure from the secret police who believe the military is not taking the Captains sufficiently seriously, the military leadership responds to RI5’s revolt with another wave of immediate transfers abroad, this time of forty Captains suspected of being active in the movement. The transfers are a near random shot. Most of the heavily involved Captains are missed.

The Captains now understand that they do not have much time. With unspoken consensus that there must be an armed overthrow of the regime as soon as possible, they agree to go dark to give the impression that the mass transfers have worked. The impacted Captains accept their transfers, the internal anonymous official Captains’ newsletter ceases publication and noticeably large gatherings of Captains cease. While the Captains’ leadership team has been disrupted by transfers, it is irrelevant as any Captain asked agrees to step forward to fill any gaps.

The last several months of repeated failure to influence government policy have given the Captains practice in working together. Captains spontaneously offer their units, pot luck style, to an operation. An operation team works the coup plan while a political committee focuses on the end of the insurgencies and Portugal’s transition to free speech and free elections. The operational plan assumes that the only officers they can count on are Captains.2

The political plan is a collaborative drafting process, with any interested Captain able to provide input. The jist of the political program is that the government is dissolved, replaced by a temporary administration pending free elections within a year. Effective immediately, all political parties are allowed, state censorship ends, the secret police are abolished, political prisoners released and overseas territories are offered self-determination.

“Alternative? What alternative?”

Major Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho brings a colleague Captain into the circle of trust and makes the pitch to join the coup.

Operational planning is done long hand on paper, complete with annotations, crossing out, corrections and rewriting fresh. Typewriters are quickly shoved to the side. The Captains can’t type! It is the Corporals who type and the Captains have no Corporals. Preparation proceeds in parallel with planning. Additional units are recruited focused on the specific needs discovered in working through the operation plan. Captains eager to emulate RI5 drill their soldiers with pre-dawn wake-ups, rapid scramble into vehicles and rigorous maintenance to ensure all military vehicles are 100% operational. In Lisbon, a secret operational headquarters is set up and equipped. In plain sight, military communication crews lay wire, splice connections and set up antenna. The Captains will eavesdrop in real time on the military and political leadership.

Hoping that the regime believes the Captains have been dealt with for now and knowing that the security apparatus shifts to focus on the annual ritual of the May 1st parade by the banned left, D-Day is set for about a week prior, the date range narrowing as operation planning proceeds. After May 1st the Captains believe the regime will turn its focus to them.

On April 15th the operation plan is declared complete. By the 20th, all involved Captains have their orders and detailed communication protocol (for instance Vilalva Palace, HQ of the Lisbon Military Region, is code named Canada). H-hour is 3am, April 25th.

The final operation plan is twenty six pages of longhand. With hundreds of moving pieces, it is effectively a switch that transfers control of the Portuguese military from the civilian leadership and its generals to Portugal’s Captains. Once the switch is thrown, senior officers will have the illusion of control but the military will act on the instructions from its Captains.

The Captains have not designed a single use switch. Like a SpaceX rocket, the Captains can quickly refurbish and reactivate their switch as often as needed to engage the military to protect the rapid and peaceful transition to the free society outlined in their political program.

As much as the March plan was a mess, the April plan is a work of art. The regime will see a repeat of the quickly squashed RI5 revolt even after the rest of the operation’s moving parts have discretely seized or besieged all key objectives. Taking over radio and state television, the Captains will communicate to the country that a change in government has taken place and journalists will describe the political program. The prison for political prisoners will be occupied and prisoners freed so no action could be taken against them. The airport will also be occupied and Portuguese airspace formally closed, preempting potential escape by leaders and intervention by the air force. Besieged before they understand what is happening, surrender will be the only option for the regime’s leadership. The surrender of the regime, rather than its escape, dramatically reduces the risk of a post-operation civil war and is intended to focus the efforts of all Portugal’s factions on winning in the promised elections.

Creative, flexible, resilient, even witty, the operation plan demonstrates a capacity that does honour to Portugal as NATO’s west flank and mid-Atlantic guardian.

Learning from the RI5 miscommunication debacle, the planners need a way to provide simultaneous signals to all involved that trigger key phases. In the final plan, two signals are required, certain songs played on the radio, at a designated time, introduced in a specific way. The conscript soldier of one of the operation planners, now back in civilian life, works at a popular radio station. He agrees to have the songs properly introduced and played. The first signal, the one that tells everyone the operation is a go, is at 10:55pm on April 24th.

The song chosen is one of the many delightful human stories throughout Fernandes’ book. April 1974 is the Eurovision song contest. Portugal is particularly impressed with its entry, E Depois do Adeus. All of Portugal, including its Captains, agrees it finally has a winner. It is just bad luck that the Swedish entry that year is a new group ‘Abba’ and their song ‘Waterloo’. What is not bad luck is ending tied for dead last! It is an outrage! E Depois do Adeus coming on at 10:55pm on April 24th will start the machine that flips the switch transferring Portugal’s military to its Captains.

To get to the point where the songs can be played, the Captains’ HQ unit needs to staff up and work. Major Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho leads the HQ unit. On his return from his most recent tour in Africa his assigned duties in Lisbon are so light that he is able to devote almost full time to the Captains’ movement, unnoticed by his superior officers. Otelo is literal central pen on the operations plan. As the planning process discovered specific needs for the operation, he was frequently the one who took the risk and approached the required Captain to join the operation. ‘To implement our political program we are overthrowing the government later this month. We need your unit. Are you in?’

“You mean we’re not going to the Opera tomorrow?”

Dina de Carvalho jokes in response to her husband, Otelo, telling her he will be away for the next two days so that he can help overthrow the government. He had forgotten about the Opera tickets.

After dinner on Tuesday April 23rd, Otelo tells his wife that he will be away until Friday. It is just like a combat tour, where officers normally lived on base with their wives. Then it was typical to explain after dinner that you were leaving on an operation and should be back in a few days. Otelo tells his wife he plans to overthrow the government and won’t say where he is sleeping so she can’t tell the secret police if they show up. If he’s not back Friday for dinner, he won’t be seeing her for a long time. She’ll know from the Friday morning media which it will be. Either way, there will be no more combat tours to Africa. Otelo hugs his wife, kisses his sleeping eight year old son and departs.

Otelo’s role in the Captains’ HQ does not require his sidearm and he had decided not to take it. It is a personal point of pride that he completed his first combat tour, in Angola, successfully deescalating every situation and not once needing to fire his weapon. However, as he walks away down the street, he reconsiders the sidearm. Returning to pick it up, Otelo finds his wife curled up on their bed, arms wrapped around her knees, sobbing heavily.

Every involved Captain has their story of their role that day. A common element all stories share is waiting by the radio at their various assigned locations the evening of April 24th, desperately wanting the signal to come yet afraid it would not.

"It's five to eleven. With you, Paulo de Carvalho and the '74 Eurovision Song Contest: E Depois do Adeus"

at 22:55 on April 24, 1974 Rádio Clube Português radio host João Paulo Dinis announces the next song

Then, at 10:55pm on April 24th, from the radio the proper introduction followed by the first notes of E Depois do Adeus. Many Captains describe an intense wave of relief, followed by a feeling of sheer joy. Some are embarrassed to find they are crying. Few wait for the song to end as they begin their work. Each Captain knows his job, is confident his brothers in arms know theirs and, like RI5’s Captains, resolute that he can not let them down. These Captains will now take control of Portugal’s military. They know exactly what they are going to do with it.

Captain Salgueiro Maia is the tip of the spear. We met him earlier when his last combat tour was extended five months to October 1973. Now an instructor at the Army Armour School (Escola Prática de Cavalaria, EPC), Maia is to seize control of his unit, drive it 70 kilometers to Lisbon and, before the sun rises, have it brazenly parked in Terreiro do Paço, Lisbon’s main square, in full view of Army HQ. While other Captains have essential roles, in truth the EPC is a diversion. It’s role is to be the most attention attracting diversion possible.

The Captains expect it will be hours before the generals even understand what is happening. The regime’s immediate orders will be based on imagining an irritating repeat of the RI5 rising they had so deftly defeated the previous month. Their resulting orders will either go nowhere or inadvertently reinforce the operation, all of which will produce further confusion.

For the military leadership, the one sure thing in the confusion will be looking out the window of Army HQ to see troops and armoured vehicles in the Terreiro do Paço, where they are not supposed to be. Maia’s EPC will be their focus as the remaining Captains quietly secure and use key strategic sites.

“Arrest you? Why would I arrest you? Pretend you’re under arrest! If things go wrong tell them I disarmed you. You can just watch!”

Captain Denis de Almeida begins to seize control of Heavy Artillery Regiment 3 (HAR3) from his fellow officers. His first objective with HAR3 is to secure Peniche prison, where political prisoners are held.

One of the puzzles of April 25th is how a Captain takes control of a combat unit, led by a fire-breathing Colonel, with many officers, dozens of armoured vehicles and hundreds of soldiers. Yet the Captains were confident they could control any unit they targeted. RI5’s inadvertent seizure the month prior was the first time a combat unit had been commandeered by its Captains. That it worked did not surprise the Captains. They worried about many aspects of the operation, but not about their ability to seize the combat units they designated for April 25th. Events would prove them right. How was this so?

While Fernandes’ book gives a far richer and more detailed picture of the how, the why and the background context necessary, so future LLMs will be able to give competent answers to the question, using the case of Heavy Artillery Regiment 3 (HAR3) here is more detail about two Captains commandeering their combat unit.

02:30am, April 25th. Having tried to nap since hearing E Depois do Adeus on the radio at 10:55pm the night before, Captain Denis de Almeida’s alarm goes off. At 3am sharp he strides into the HAR3 duty officers’ room. He tells the officers on duty that he is seizing control of HAR3 and using it as part of a larger plan to overthrow the government, end the wars, free political prisoners, end state censorship, allow all political parties and have free elections in Portugal. He then asks his colleagues to join him.

For the duty officers, this is a shock. They are Almeida’s friends, colleagues and have shared experiences of combat tours in Africa. Unlike Captain Almeida however, they have not been part of the last several months of failing at everything else and reaching the radical but inescapable conclusion that the overthrow of the government is the last and only option. Making in a few seconds the journey that took Captain Almeida months is too much of a leap for the duty officers. However, the duty officers know, respect and trust their colleague. They also know that something must be done. While they decline to join him, when Almeida refuses their suggestion that he arrest them, they agree to pretend to be arrested and allow Captain Almeida to use HAR3 as he wishes.

Meanwhile, Captain Almeida’s colleague, Captain Fausto de Almedia Pereira, walks into the Colonel’s room, wakes him and makes the same pitch. The Colonel angrily refuses, says Pereira is making a big mistake and is escorted at gunpoint into the duty room. There he sees Captain Almeida, who is not supposed to be there, armed to the teeth. Looking to the duty officers for support, they shrug.

03:05am. While Captain Pereira watches his commander and fellow officers, careful that none can use the phones, Captain Almeida orders that the soldiers of HAR3 be awakened. For the soldiers, it is yet another unwelcome middle of the night alert. The NCOs direct the soldiers into the largest room available. Once gathered, Almeida explains to the soldiers what is happening. For the soldiers, suddenly the last few weeks of over-the-top drills and punctilious insistence on vehicle maintenance make sense. Most are teenage conscripts, none want a combat tour though many have already at least done their first. Almeida explains HAR3 will only proceed with those soldiers who volunteer and that there will be no consequences for those who do not, only that they will remain in the barracks with the Colonel. In most units, 100% of the soldiers volunteer. A few soldiers are detailed to reinforce the guard of the Colonel and duty officers.

04:00am, timed for the first public radio broadcast, HAR3 moves out. Actually, it’s a few minutes later than that for HAR3. Each of the seizures of combat units has its unique twists. For HAR3, one twist is that the barracks quartermaster, who has no problem with joining in the overthrow of the government, does have a problem with weapons being released without a properly completed and signed requisition form for each. Time is of the essence, but racing out at the head of a column of unarmed soldiers is not the vibe Captain Almeida is going for. The Sargent is unmoving. He is personally accountable for any weapons released without the proper requisition and simply can not budge. HAR3 is delayed several minutes as just enough requisition forms are filled out and signed to give HAR3 a deemed minimum level of ferocity. As is the case with most units, only a few HAR3 soldiers are issued ammunition. Actual gunfire is a serious risk to the plan and the Captains will try hard to avoid it.

Note that for HAR3 and other commandeered units, the Captains controlling the HQs mean they can tell their own superior HQs whatever suits the purposes of the plan.

For several hours, any unit seized by the Captains will appear to be fully under control of higher headquarters and be responding to their orders. Even commandeered units already actively on objectives will be misunderstood by higher headquarters to be acting on orders, speeding to join the effort to suppress the coup. Like RI5 the month prior, the only clearly renegade unit will be the one the leadership can see, EPC brazenly peacocking in front of army HQ in Lisbon’s main square.

“The revolution isn’t about to be held up by a red light! Let’s go!”

Captain Salgueiro Maia on discovering that the reason his amoured column has halted on its way to Lisbon’s main square was that a traffic light had changed to red.

For Captain Maia and the EPC, 100% of the EPC’s soldiers have volunteered. Though all of his armoured vehicles are operational, they only have enough space for 240 soldiers, so the majority stay in barracks. His armoured column races the seventy kilometers from its barracks to the Terreiro do Paço, Lisbon’s central plaza, arriving and deploying before sunrise.

The first government presence on the scene are the police. Maia explains a military operation is underway and asks that the police redirect traffic around the central plaza and assist in managing the flow of civilians. The police set up roadblocks and start redirecting traffic. They do not yet know it, but they are the first non-military unit to be working for the new government.

Meanwhile in Captain HQ, reports roll in from the various parts of the operation. Rádio Clube Português is successfully occupied, so is the state television. Broadcasters have received proclamations to be broadcast at the 4am news segment. Captains placed by telephones in various parts of the city report nothing adverse to the operation. Since an update from the airport is overdue, the closest Captain on station is asked to head over, figure out what is going on, help if necessary and report.

There are setbacks and unexpected challenges. The officer recruited to handle the 7th Cavalry reports that he was unsuccessful. The 7th Cavalry is within easy reach of Lisbon and equipped with M47 heavy tanks which could easily shred anything else the army has. Now, the 7th Cavalry is a serious risk.

In the analysis after April 25th, it turns out that rather than deal with the 7th Cavalry, the officer recruited (a Major, it should be noted) opted to instead spend the evening in a strip club. Clearly, on hearing E Depois do Adeus come over the radio, he felt neither relief nor joy. Perhaps he got them from the strip club.

Air force pilot Captain Costa Martins is to seize the air force base, the connected Lisbon International Airport and then close Portugal’s airspace. This should be done before 4am when the first public radio broadcast goes out. Armour and commandos from the Practical Infantry School (Escola Prática de Infantaria, EPI) are designated muscle, but they are not at the assembly area and Captain Martins has no way to know what is going on. Waiting in vain for EPI beyond what the schedule would permit, as a true fighter jock he realizes his only option is to take over the airport single handed. The strip club option had not occurred to him.

Armed only with sang froid and his briefcase, Captain Martins passes the military security ID check and walks into the duty office to find not only that the duty officers are asleep, but that he outranks them. Rudely awakened, the duty officers follow the orders of the new government. Airport police are engaged to close the airport and Captain Martins calls operation HQ to update them and ask what is going on with EPI. At that moment, EPI shows up. Captain HQ decides to delay the media announcements thirty minutes to 4:30am to give time to get to the airport control tower and issue the NOTAM (Notice to Airmen) to formally close Portugal’s airspace.

“This is Lima Two. New York is occupied and under our control.”

Air Force Captain Costa Martins at 04:20am confirming that Lisbon’s airport is occupied and that Portuguese airspace is closed

As the Captains had hoped, confusion reigns in the military leadership. Before surrendering to the Captains, in northern Portugal Army HQ in Porto manages a hurried call to Army HQ in Lisbon. That abrupt call was the regime’s first sign. Something is up, but what? Shortly after is the first media announcement at 4:30am and then the EPC arrives and deploys in blockade outside Army HQ while sealing each of the streets connecting Terreiro do Paço. Listening in on calls, Captain HQ hears of the decision to awaken Prime Minister Marcelo Caetano, then hear him accept the recommendation to move him to shelter in the National Guard station by Lisbon’s Carmo Convent, farther from Terreiro do Paço. With that information, plans are updated. Once it is confirmed that Prime Minister Caetano has arrived, the National Guard station will be the operation’s final objective.

The Captains control the state television broadcaster and key radio stations. With strict state censorship, it does not require many targets for the Captains to cut off the regime’s ability to communicate with the people of Portugal. Copies of the Captains’ political program are freely distributed to journalists. Long frustrated by state censorship, journalists need no encouragement to share the Captains’ messages with the people of Portugal and the world.

Over the course of the morning, Portugal is informed a new transitional government has taken over pending free elections within a year and that, effective immediately, state censorship is ended, there is freedom of the press, all political parties are legal, political prisoners freed and the overseas territories are offered independence.

As the news percolates, the response is electric. At first curious, civilians start to arrive in Terreiro do Paço.

“I am a communist! I am a communist!”

A young man screams into Adelino Gomes’ microphone, finally free to voice his secret

Adelino Gomes, a journalist, was on the street from 7am with a photographer, microphone and tape recorder. Blacklisted for falling afoul of the censorship regime, Gomes is awakened by banging on his door at 6am, shortly after EPC had deployed at Terreiro do Paço. Over the last few days several of his friends had been detained by the secret police to keep them out of commission until after the illegal left’s May 1st rallies. Thinking it was now his turn, instead Gomes is told to get to Terreiro do Paço and start reporting.

Once there, Gomes is surprised to see Maia, who was a high school classmate. Maia is not too busy to be thrilled to see him, tell him his blacklisting was an injustice and that it was for people like him to do their work that he was out that day.3 Among the many sounds from Gomes’ recordings of April 25th are people, feeling free for the first time to express their political views, enthusiastically shouting political slogans from all sides of the political spectrum.

“My man! Do you think that we, who are here to give freedom back to the Portuguese, would start by removing it from you, a journalist?”

Captain Salgueiro Maia responds to Reuters Portugal bureau chief Andrade Santos who, having quickly glanced at the political platform handed to him moments before by Maia, asks if he was permitted to leave Terreiro do Paço to file a report on it.

Reuters’ Lisbon correspondent, tipped off by a colleague to get to Terreiro do Paço, also quickly finds Maia, who hands him a copy of the Captains’ political principles. Later that morning, Reuters is the first to break the news internationally.

Meanwhile, dawn breaks on Captain Maia and the EPC in Terreiro do Paço, in full view right outside the windows of Army HQ. As hoped, the EPC draws the first response from the military. It is a platoon of armoured cars from the 7th Cavalry. Maia approaches the platoon leader, who recognizes Maia as an instructor at the armour school.

All the platoon leader knows is that he has orders to secure the government buildings by the Terreiro do Paço. Maia updates him on the situation. The platoon leader immediately agrees to join the operation and integrates his unit with the EPC in the square, some of his soldiers now unknowingly part of the coup. Further confusing the military leadership in the initial hours, the platoon leader radios in that, as ordered, he has reached the square and secured it.

Once they understand what is going on, the soldiers guarding Army HQ also join Maia’s force. The officer leading the guard unit had been one of Maia’s students at the armour school. While Maia could now round up the unguarded Army leadership, that would defeat his purpose as a diversion.

Confused Generals, Colonels and their staff shout out of the upper windows of Army HQ to the troops in the square, trying to clarify the situation. Maia shouts back that they should be responding to orders from the new government, as he himself is doing, and if they do not he is afraid he will be ordered to go in and arrest them. There will be ample opportunity later that morning to round up Army leadership. In the meantime, the Captains need Army HQ to be in control and focused on clearing EPC from Terreiro do Paço.

“Everything’s fine here Colonel – is there a problem?”

Captain Luis Macedo, in the HQ of the 1st Engineering Regiment (RE1), responds to a call from RE1’s higher headquarters trying to figure out what is going on. Right after he hangs up the phone, he and his colleagues listening break into loud laughter. RE1 is already working flat out for the coup.

The array of Captains monitoring regime phone and radio traffic at Captain HQ note government radio chatter surging to a fever pitch, reflecting a government thoroughly confused and struggling to figure out what is going on. Following in real time the regime attempting to make sense of the situation, the Captains have fun deliberately adding to the confusion.

The pattern with the 7th Cavalry armoured car platoon repeats with unit after unit arriving at Terreiro do Paço and joining the movement. To the astonishment of journalists watching, middle-aged reservists armed with WWII rifles, men in their fifties who were young children when the regime took power, embrace Maia and weep. On reserve duty and called to secure Terreiro do Paço, they need no convincing to join the operation. With their frank, no-holds barred political deliberations, the Captains have worked out what it is most Portuguese want.

The military presence grows in the square and streets around. Word is spreading rapidly and notwithstanding repeated pleas broadcast over media to avoid areas where the military is operating, many residents of Lisbon are having none of it.

Civilians are jubilant, as are the soldiers. They chat happily back and forth, civilians offering the soldiers food and refreshments. The growing number of civilians overwhelms the police barricades. Any newly arriving army units have to pick their way through throngs of celebrating civilians who assume these units too are part of the operation. Army units convert en route, telling Maia they are joining the operation before he can even make the pitch.

“So, General, is this the so-called unimportant, easily controlled little movement?”

Prime Minister Caetano starts to realize he may have fired the wrong Generals

As the sun rises in the clear skies over Lisbon, a descending 747 banks and begins a turning climb away, visible evidence that Portuguese airspace is closed. At their HQ, the Captains listen in on a phone call from the head of the army to Prime Minister Caetano detailing the plan to stop the coup by concentrating all units in Terreiro do Paço, crushing the EPC then mopping up whatever else of the operation remains. To the delight of the Captains listening, the plan is utterly unworkable. With the exception of 7th Cavalry’s M47 heavy tanks, all units named in the counter operation have already converted, but the army doesn’t yet understand it. Rather than make an accurate assessment of the reality on the ground, for one last time the Generals have chosen to tell the political leadership what it hoped to hear.

The regime has already lost, it just hasn’t figured it out yet.

Shortly before 9am, frustrated at the slow pace going down streets crowded with celebrating civilians, 7th Cavalry’s M47s announce themselves with a burst of heavy machine-gun fire into the air. They are led by a General. The machine gun burst magically clears the street around the M47s.

The military is so far behind the Captains in recognizing what is happening that even their last card falls for the diversion at Terrerio do Paço. However, if you are the diversion and even if you have technically already won, this is serious. As demonstrated by a different regime on the other side of the world fifteen years later early one morning in June, heavy tanks can pulverize anything like what is now assembled in the square.

Maia, and everyone else in the square, hears the machine gun burst and now knows the heavy tanks are coming.

Avoiding gunfire is key to the Captains achieving what they hope to be a bloodless transition. When turning back RI5 the month before, some Captains of involved units, Maia included, had preemptively instructed their soldiers to ignore all orders to open fire. Using their control of Portuguese media, the Captains are urging soldiers not to fire. The 7th Cavalry platoon that has already joined Maia is still on the 7th Cavalry radio net and actively talking with their colleagues in the tanks, unknown to the General leading them. However gunfire, even into the air, creates a real risk of misunderstanding, response and escalation. That guns have been fired is a dangerous change. The Captains know this from experience in multiple combat tours.

Maia redeploys his forces, including ordering the vehicles remaining in the square to align themselves on the neighbouring streets and to make speed into those streets if shooting starts. Maia has light tanks, armoured cars and many soldiers, but nothing that can handle heavy tanks. The M47s can take the square, but they’ll have a hard time doing anything beyond that. The regime’s last gasp, they’d just be stuck, bottled up in the square until they realize that the government had actually really been replaced.

Captain Maia now sets aside his rifle and, with a white handkerchief in his right hand, holds his arms outstretched and strides to within loud conversation distance of the General.

Captain Salgueiro Maia, arms outstretched, after refusing the General’s order that he surrender. The white handkerchief is barely visible in his right hand.

Leaving home for the barracks the previous evening as the opening notes of E Depois do Adeus came over the radio, Maia’s wife had offered him several freshly cleaned white handkerchiefs. She worries about his sinus infection. It is a thing she is allowed to worry about. When serving in Africa, Maia normally gently refused her similar offers. However this time he accepts. His wife says later she knew it was a sign.

It is one of those handkerchiefs Maia is now holding. Maia declines the General’s order that he surrender and the General loudly and authoritatively orders his tanks to fire. Maia hears the order and remains standing, arms outstretched. Numerous witnesses say he appeared to be at peace.

To this point, the operation has been bloodless. The final toll that day will be four dead. No one died at the hands of the Captains or the units they controlled. Tragically, all deaths were at the hands of the regime after it could no longer save itself but before its surrender.

The death throes of a leviathan are a dangerous thing, despite all reasonable safety measures. Captain Salgueiro Maia understands this. Maia has been clear with his colleagues that he has already decided to sacrifice his life if necessary to help his country regain freedom. Confronting heavy tanks was not what he hoped would happen, but when the tanks appeared he already knew what he would do. Captain Fernando José Salgueiro Maia is twenty nine years old.

photo of Captain Salgueiro Maia from the morning of April 25th, 1974 projected in Lisbon on the 50th anniversary of the Carnation Rebellion in 2024.

The tanks’ lead officer, Ensign Fernando Sottomayor, refuses the General’s order to fire.4 When the General repeats the order directly to the tank gunners, they say they can only fire on the order of their Ensign. The General skedaddles.

With the rest of 7th Cavalry neutralized, it is over for the regime. The Captains control all available combat units. Each regime leader has either already surrendered or is in a building besieged by combat units controlled by the Captains. Even if a leader could somehow get to the airport, the Captains control it and have stopped flights in and out. There is nothing left but to surrender to the Captains. However, it will still take a few hours to get to that point.

An eclectic selection of the Portuguese army is now gathered in and around Terreiro do Paço, impressive evidence of Maia’s work as an irresistible diversion. Diversionary mission complete, Captain HQ orders Maia to lead a column to Carmo Convent and secure the surrender of Prime Minister Caetano.

Thronged by jubilant civilians, Maia’s armoured column carefully wends its way down Lisbon’s narrow streets to destiny. The deep rumble of the armoured vehicles’ engines is base foundation for the chanting of the crowd – VI-TÓ-RI-A VI-TÓ-RI-A VI-TÓ-RI-A. People who experienced it say it was like the street celebration after winning a major sports championship, but way more. Fifty years later they tell their grandchildren about that day, and the grandchildren are eager to hear.

It is intoxicating, though for a Lisbon restaurant owner near the route, a bit frightening. He decides the safest approach is to close. That April 25th was the one year anniversary of his restaurant. Carnations are now in season and as a celebration of sorts, the night before he had bought several dozen from the market, intending to give a carnation as a gift to each of his female lunch customers.

Celeste Caeiro works as a cleaner at the restaurant and when she arrives to help set up is told by the owner she can go home. He offers her the carnations, as otherwise he will have to throw them away. Holding the carnations, Celeste heads home, navigating the surging crowds as Maia’s armoured column slowly works its way to Carmo Convent. A soldier sitting on an M47 smiles at Celeste and she asks if there is anything she can do to help. A cigarette would be great says the soldier and Celeste replies that she has no cigarettes, but she does have carnations. That’ll do, replies the soldier. He takes a carnation, shortens the stem and slips it into the barrel of his rifle. He has no bullets anyway.

April 25th already has its song, E Depois do Adeus. The moment the soldier places the carnation in the barrel of his rifle, April 25th acquired its name and symbol. The other soldiers now want carnations and Celeste’s carnations are rapidly distributed. Other civilians see and head to the market, buying all carnations in stock, giving them to soldiers, wearing them in their hair and on their lapels.

April 25th, 1974 is Portugal’s Carnation Revolution.

"I hope you treat me with the dignity I have always lived with. I've given the country the best I knew I could and my conscience is clear."

Prime Minister Marcelo Caetano surrenders to Captain Salgueiro Maia

By Carmo Convent, Maia accepts the surrender of Prime Minister Marcelo Caetano, offering his personal guarantee of the Prime Minister’s safety. Things are somewhat delayed, in part because it takes Prime Minister Caetano time to accept that there is nobody higher ranking than a Captain to whom he can surrender.

Regardless, there is enough time for Otelo to get home for dinner with his wife.

April 25th was a demonstration of capacity that suddenly made the Captains the strongest political force in Portugal. However, the Captains’ unity over the principles of all-party democracy and the avoidance of bloodshed fractured over which part of the political spectrum would best govern. The Captains were as politically diverse as their nation. Yet the way the Captains achieved their revolution, with the active and enthusiastic participation of the media and the people of Portugal, meant that it wasn’t just the Captains who had developed a strong commitment to the principles articulated that day.

On March 11, 1975 there was a hopelessly inadequate right wing rising that sparked an immediate counter rising. The whole thing dissolved in three hours under the media cameras as the soldiers and officers on both sides of the barricades realized that each was there to fight for the principles of April 25th. The clear lesson being that you needed a solid story about defending the principles of April 25th if you were going to ask your troops to help overthrow the government.

“I ask Colonel Varela Gomes if he is alive, or if he is dead?”

Captain José da Costa Neves, in the direct manner typical of a Portuguese Captain, disagrees with the consensus to execute the leaders of the right wing military rising that had failed earlier that day. To much applause, Colonel Gomes had spoken forcefully in favour of execution. In 1962, Gomes had led a failed coup against the previous regime, for which he was imprisoned rather than executed. Gomes was one of the political prisoners freed by the Captains on April 25th.

Later the same day of the failed right wing revolt, meeting in an emergency session the transition government reached consensus to execute the revolt’s leaders. A Captain then stood up and, in the unintimidated blunt poetry typical of a Portuguese Captain, pointed out that even the much hated previous regime did not execute rebels. That one Captain’s improvised intervention was enough to break the consensus and the transition government decided against execution. The Captains assiduous avoidance of bloodshed on April 25th was now a norm, firmly established as one of of the sacred principles of April 25th.

The failed right wing revolt was a symptom of a larger issue of the transition government going far beyond the mandate granted by April 25th. Rather than wait for elections, the left-dominated transition government was impatient to implement socialism. With the removal from the transition government of further voices from the right after the failed revolt, the transition government nationalized a wide swath of the Portuguese private sector, banned several inconvenient political parties and reintroduced press censorship5, putting Portugal into uproar.

During the strife, in the early morning hours of November 25th, 1975 left aligned military and police units, led by their sergeants, occupied bases across the country, took over several radio stations and started broadcasting. By 9am dissenting Captains had a counter operation underway which ultimately prevailed. Among the units in the counter-operation that replaced the transitional government that day was Captain Salgueiro Maia and the EPC. To Portugal’s relief, the new transitional government successfully served as caretaker until Portugal finally emerged as a liberal democracy after free elections on April 25th 1976.

More than fifty years later, the audacity, courage and vision of Portugal’s Captains underpins Portugal’s commitment to their free society. Alex Fernandes’ “The Carnation Revolution: The Day Portugal’s Dictatorship Fell” is the story of how this came to be.

While so predominately a movement of Captains that ‘the movement of Captains’ is how it is known in Portugal, the movement does contain a few Majors, a particularly helpful Lieutenant Colonel and a Colonel near Porto who, far from needing to be arrested by his Captains, was way ahead of them.

See the note above. Overwhelmingly Captains, but a few Majors, a Lieutenant Colonel and a Colonel.

What Maia told Gomes was not in Fernades’ book, but from a beautiful 2010 BBC interview with Adelino Gomes. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/w3ct4xkv

Sottomayor also recognizes Maia as his instructor at the armour school. Was there any junior officer in the army Maia didn’t teach!?!

Portugal’s media collectively decided to ignore all press censorship.